The summer of 2025 marks the 1700th anniversary of the famous Council of Nicaea. What happened during the hot months of AD 325 in the little town which is today called Iznik, Turkey? Why do the theological concepts debated there by three hundred bishops matter so much for Christians in the modern world? And why do we still recite the council’s Nicene Creed—in a slightly later, adapted form—as orthodox doctrine that believers everywhere must endorse or be called a heretic?

Though the events that transpired at the council—and even its precise location in Nicaea—remain shrouded in mystery, historians have a full grasp of the theological issues under debate. Not only did the ante-Nicene church fathers leave an ample record of the issues that set the table, the council fathers and their opponents continued their arguments for six more decades beyond the summer of 325. The written legacy of the theological controversy leaves us in good position to understand what was going on.

At the heart of the matter was the doctrine of the Trinity. The word trinitas first appeared in the Latin writings of the church father Tertullian around AD 200, a century and a quarter before the council. Prior to him, no Christian writer had used this expression to describe how God could be three and one.

However, starting in the second century some Christians had used the term trias—the normal Greek word for the number three, or a triad—to denote God’s tri-unity. Though most of the theological attention focused on the Son’s relationship to the Father, the whole matter was framed in a triune way because every Christian was baptized into God’s threefold name. Jesus had said, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19). The church’s baptismal practice inevitably made Christians think in terms of three. The tricky question was: How do we remain monotheists while accounting for the distinct personalities that Scripture ascribes to God?

The run-up to the Council of Nicaea started in Egypt. A local presbyter named Arius tried to preserve monotheism by investing only the Father with fullest and most perfect deity. He alone, of all beings, had no source or origin. The Son was, according to Arius, a glorious creature with lesser divine status. Since the Son wasn’t eternal but had a beginning in time, he wouldn’t disrupt Christian monotheism. Only the Father was truly God, while the Son was an exalted, semi-divine creature whom God had made.

But the opponents of Arianism—especially Athanasius of Alexandria—said demoting the Son like this would destroy the gospel. Theological language had to be developed that would preserve his total equality and eternity with his Father. The Nicene Creed solved the issue by harnessing a key Greek word: homoousios, which means “of the same substance” (homo = same, ousia = substance). Using Latin-based words, we can express it as “consubstantial.” If the Father and Son—who were the initial Trinitarian persons under discussion, not the Spirit—shared the same substance, there could be no time when one existed without the other. They must be co-eternal and both fully divine.

Athanasius of Alexandria

Shared substance indeed created a close association. What, then, would preserve their distinct personalities? In the decades after the council, the Greek word hypostasis came to define the three individual persons within the Godhead. This followed the previous example of Tertullian, who had used the Latin term persona to describe the same idea. The Nicaea-supporting church fathers—especially the Three Cappadocians: Gregory of Nazianzus, Basil of Caesarea, and Gregory of Nyssa—refined the meaning of hypostasis to denote the distinct Trinitarian personalities who could know one another and interact back and forth.

By the time of the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the term hypostasis had crystallized to define Christ’s distinct personhood. Along with the personhood of the Father and the Spirit, this gave a Trinitarian formula of three distinct hypostaseis sharing a single, unified ousia. Ever since then, proper Nicene dogma has articulated one divine “substance” or “essence.” Yet the monotheistic God exists as three distinct “persons” who comprise the Trinity. How exactly this works is a mystery! Yet this is what orthodox Christians must confess to embrace the biblical and historic doctrine of God.

Analogies of the Trinity

Since the Trinity is fundamentally mysterious, many believers through the ages have tried to explain it by using analogies. A well-meaning Christian apologist might display a hard-boiled egg to Trinitarian skeptics. “This is a single object, is it not?” he asks his listeners. When they agree, he cracks it, peels it, and takes it apart. Shell fragments, the white, and the yolk are now separately visible. “You see?” the apologist exclaims triumphantly. “A single object can have three parts! So, too, does the Trinity.” And if his audience isn’t convinced, the intrepid apologist can go on to display the peel, flesh, and core of a single apple—another commonly-used analogy of the Trinity.

Does this illustration work from the perspective of strict theological orthodoxy? Like any form of analogical language, it explains the truth, yet does so imperfectly. The core idea is acceptable: a conceptual singularity can have a triple aspect inherent within it. But that is as far as the illustration goes. Any attempt to push it further will devolve into heresy. The shell, white, and yolk are each one-third of the egg; but the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit aren’t thirds of God. The hard-boiled egg that we eat—sans its shell—is reduced to a two thirds existence. So is the apple’s peel and flesh without the core. With God, however, the three persons of the Trinity are each fully God, inseparable, irreducible, and indivisible. Therefore, the egg and the apple are imperfect illustrations of the Trinity. They can start someone thinking the right way, but they can’t encapsulate proper doctrine in all its particulars.

Nevertheless, people have always tried to use Trinitarian analogies, starting with the ancient church fathers. Some were based on observable natural phenomena, others on objects, still others on personal relationships. When something as mysterious and unique as the Trinity is under discussion, it’s only natural for its defenders to illustrate it with concrete realities that everyone can understand. Analogies of the Trinity serve a good purpose, so long as we don’t press the details into heretical dead-ends.

It’s precisely because the analogies work up to a point, yet ultimately fail, that they can help us understand the ancient doctrine of the Trinity. By assessing the analogies for their merits as well as their flaws, we develop a deeper appreciation for what the Trinity is all about. So let’s take a look at some Trinitarian analogies as a way to understand what the early church fathers were debating at the Council of Nicaea. The most often-used analogies can be divided into four basic categories: physical objects, dynamic processes, personal relationships, and mental reasoning.

Physical Objects

In addition to the already-mentioned egg and apple, a common object used to illustrate the Trinity is the Irish shamrock. St Patrick supposedly resorted to this illustration with his pagan converts, though there’s no evidence for that in his writings. Even so, a plucked shamrock is a single entity which has three distinct lobes. This illustration works better than an egg or apple because the three parts are more similar to one another. They share the same essential substance—leafy plant material—instead of being diverse like eggshells and yolks, or an apple’s peel and its flesh. Because of the shamrock’s identity of substance with three distinct nodes of differentiation, it isn’t a bad illustration. If Patrick or some other Irish missionary used it in evangelism, kudos to them!

Another object which I have sometimes used to illustrate Trinitarian ideas comes from my upbringing in the 1970s: the child’s toy known as the Pyraminx. Like the Rubik’s Cube but pyramidal in shape, this puzzle has multicolored facets that can be scrambled and reconfigured so the three visible sides each have their own colors. When solved, the Pyraminx constitutes a single object sitting on a table. As we walk around it, we perceive its faces as distinct, depending on our point of view. Yet anyone would agree it is only one item: a coherent whole with three modes of presentation.

And therein lies the problem. I typically use the Pyraminx to illustrate the ancient heresy of modalism. Originally, this false view of the Trinity was known as monarchianism or Sabellianism (after one of its early advocates, Sabellius). The twentieth-century German historian Adolf von Harnack called it Modalismus and the name stuck. But the ancients called it monarchianism because the word referred to a universe governed by a monarchy, that is, a singular Father God. To account for Scripture’s depictions of the Son and the Spirit, the monarchians said they were just subsequent manifestations of the same divine being. Instead of being separate personalities, they were different aspects (or “modes” in Harnack’s parlance) of God’s self-revelation as he transitioned from being known as a Father to a Son, then to a Spirit.

The theological problem with modalism is the denial of the Trinity’s interpersonal differentiation as seen in Scripture. Didn’t Jesus relate to his Father as someone other than himself? Of course he did! His prayer, “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me. Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done” (Luke 22:42) makes no sense if Jesus is addressing himself. Likewise, didn’t the Father and Son send the Spirit as someone in addition to themselves (John 15:26)? The Bible’s testimony about the personal relationships within the Godhead can’t be squared with modalism. An illustration like the Pyraminx largely fails because it depicts the Father, Son, and Spirit as three perspectival “sides” of the same being, not as distinct persons who can discourse with and relate to one another.

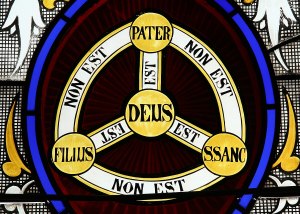

In many English churches, stained glass windows visually depict the so-called Scutum Fidei or Shield of Faith. Before it was set into church windows, the imagery began to appear in medieval theological manuscripts starting around the year 1200. The heraldic “shield” mimics a traditional coat-of-arms with three circles arranged in a triangle. They are designated to represent the Pater, Filius, and Spiritus Sanctus. Between each of them extends a line marked “is not,” while the center of the shield bears a fourth circle called Deus, or God. It has connecting arms that radiate to each separate person with the declaration “is.” Doctrinally, the shield is accurate as far as its verbal propositions go. The Father is not the Son, nor are either of them the Spirit. The shield rightly denies the conflation of persons taught in modalism. Yet in proper Trinitarian theology, all three persons are God, which the shield correctly affirms. Okay—so far, so good.

The shield’s biggest problem is its fourfold nature. According to this depiction, the Father, Son, and Spirit share in some fourth circle defined as “God”—as if there can be amorphous God-stuff in which the three persons each partake. This is a particularly Latin way of thinking about the Trinity, where emphasis is laid on the unity of substance but perhaps at the expense of the three distinct persons. In the eastern mindset, the Trinity is social and communal, so there can be no talk of God’s substance removed from the three persons who interrelate—or even, in Greek thinking, interpenetrate. While the Scutum Fidei articulates true propositions, it poorly pictures the threefold (not fourfold) architecture of the Godhead.

If I were a missionary in lands where I often needed to illustrate the Trinity, I would probably wear the Celtic-style pendant around my neck called the Trinity Knot. Its triple-lobed geometry is formed by three arcs that flow continuously into three points. If we imagine the pendant as being made of 100% gold, we could point out the complete unity of its substance. Yet someone could touch each point separately and experience three distinct “pinpricks” in succession. Clearly, there are three centers of experience, yet the substance is one. Like the shamrock, the Trinity Knot nicely illustrates oneness and threeness at the same time. Apparently, those Irish theologians really understood the Trinity!

Dynamic Processes

God isn’t static like an object, but is living and active, so the analogies work best when they bring out his animation and vigor. One dynamic transformation often used to illustrate the Trinity is the phase transition of H2O. The same molecule can begin as frozen ice, then thaw into liquid water, then boil into steam. Though the original molecule is preserved, it is experienced differently and has distinctive attributes.

While this analogy does teach unity of substance, its presentation of God’s threefoldness is problematic. Essentially, it is a form of modalism, in which the singular God is experienced first one way, then another, then a third. The phase changes of H2O don’t adequately bring out the distinct personalities of the Trinity. When ice has melted or water has boiled, the previous phase is gone. Yet when we encounter the Son or Spirit, in no way has God the Father disappeared or “turned into” the subsequent mode. The ice/water/steam analogy must be used with caution lest it convey heretical ideas.

A better dynamic analogy can be found in the toy—who knew toys could be so theological?—called the Fidget Spinner. This contraption is a kind of top which revolves at great speed. Since the Fidget Spinner has three lobes, its revolutions create a singular whirling disk which is threefold at the same time. The whirling motion has created simultaneous oneness and threeness. The dynamism of constant movement nicely illustrates how the Trinity’s lively unity is diversified into plurality.

In some conceptions of the Trinity, the sending of the Son and Spirit by the Father plays an important role. The Old Testament depicts the God of Israel enthroned on high, sending forth his Word and Breath to carry out his will in the physical realm. Psalm 33:6 declares, “By the word of the LORD the heavens were made, and by the breath of his mouth all their host.” Likewise, Jesus says he was sent to carry out his Father’s will (John 6:38), and God sends the Holy Spirit in the Son’s name (John 14:26).

Divine sending or extension is depicted in three analogies offered by Tertullian. They have often been quoted in church history to explain the Trinity. Tertullian speaks of a plant’s root, shoot, and fruit—a single organism which projects into three distinct parts. Likewise, the one sun in the sky sends forth a secondary ray which can, thirdly, land upon a surface as a point of light. Or again, one wellspring can send forth a river from which a canal extends. The three observable aspects in these analogies are part of the same whole, yet they’re arranged in a dynamic relationship of extension and sending. Just as the sun sends out its rays, so the Father sends the Son and Spirit. Such analogies work well because they convey unity, triplicity, and divine mission—all biblical, Trinitarian ideas.

Speaking of sunlight, some brainy scientists have used modern physics to illustrate the Trinity. Light from the sun consists of multiple colors that combine into unified whiteness. Certain technological devices project light beams of three basic colors: red, green, and blue. The RGB color model says that when the three colors are superimposed, they will appear as white—yet each of the constituent colors is “there” at all times, and each can be experienced uniquely when it’s separated out. Appropriately, white is the liturgical color of the Holy Trinity: a single purity that contains three fundamental colors within it.

The RGB color model

Physicists have even used quantum theory to illustrate the “both/and” nature of the Trinity. The wave-particle duality of light proves that things in the natural world can be both A and B at the same time. Light is a wave as well as photons simultaneously, not alternately or consecutively. The theory of quantum superposition also shows how particles can exist in two states at the same time in a paradoxical way. For theological skeptics with a scientific bent, such dynamic analogies might help explain how the Trinity can be seemingly contradictory—both singular and multiple—without violating the universal laws of physics.

Personal Relationships

Some ancient church fathers liked to illustrate the Trinity by appealing to individual people who shared the common substance of humanity. For example, Paul, Silas, and Timothy were three separate men who shared the property of manhood. This is really just a theological version of the philosophical distinction between universals and particulars, or a genus and its species. The Three Cappadocians taught that the word ousia provided the general, over-arching category, within which three distinct individuals (hypostaseis) existed. Gregory of Nyssa said, “You have seen how this principle of differentiation between ousia and hypostasis applies on the human level. Apply this now to the doctrine of God, and you will not go wrong.”

Although this kind of thinking contains a grain of truth, it was basically a form of tritheism. The central plaza of many Roman towns had a temple for the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. These were three cooperating deities who shared the general classification of “gods” but weren’t unified in a monotheistic way. Though the Cappadocian Fathers could sometimes use the universal/particular analogy for the Trinity, they were well aware of its shortcomings and didn’t press it into heresy. In the end, they believed it was better to keep God’s exact nature mysterious and unknowable.

The Capitoline Triad

Another relational analogy emerges when we examine a person’s life roles. A single man could be at once a husband, father, and worker. But this analogy fails because it describes only one person who is differentiated by his identities and duties; whereas the Trinity is fundamentally an interpersonal relationship. That is why a marriage between two spouses is a much better Trinitarian picture. Quoting Genesis 2:24, Jesus says of a married couple that “they are no longer two but one flesh” (Mark 10:8). Although neither the husband nor wife disappears as a separate person when they are wedded, they share in the substance of matrimony, of couplehood, of mystical unified flesh—indeed, of harmony and love. But in order for their love to be fruitful and non-exclusive, we can extend the analogy to a family, in which the parents, now joined by a child, foster a love that is tri-dimensional and therefore communal. This is an excellent analogy of the Trinity, so long as it isn’t over-interpreted to view the Holy Spirit as the wife and mother of the Father and Son!

Mental Reasoning

The great church father Augustine of Hippo lived through the culmination of the Nicene debates about the Trinity in the late 300s. By the time he turned his attention to this weighty theological topic, the doctrine of “one substance and three persons” had been firmly established. Instead of taking a hard polemical tone against Arianism in his On the Trinity, Augustine explored several analogies to explain God as three and one. Since these analogies focused on human thinking—the inner life of the psyche or soul—they are often called “psychological analogies.” Augustine advocated this approach because humans ought to naturally reflect the God in whose image they are made.

Augustine first explored the triad of Mind, Knowledge and Love. A single thinking mind has distinct knowledge within it, creating a twofold reality. Since the mind also loves what it knows, love becomes a third part of the act of cognition. Augustine then described the triad of Memory, Understanding, and Will. A single mind can remember something, understand it, and direct itself toward what it remembers and knows. Although the act of thinking is unified, it nonetheless requires a triple action. Thus the human mind has a kind of “trinity” within it.

The second psychological analogy is especially useful when we consider a mind that is reflecting on God. Then the recall of God’s actions and the understanding of his beauty will direct the thinker’s will toward the good—which results, inevitably, in acts of love. Augustine declared, “But when the mind loves God, and consequently . . . remembers and understands him, [the mind] can rightly be commanded to love its neighbor as itself.” Although Augustine ended his book with the reminder that all analogies eventually fall short, his triad of Memory, Understanding, and Love beautifully images the inner life of the Godhead. Why? Because like a human whose sanctified will results in good deeds, the Trinity always overflows with loving actions that bless the world.

What about a biblical analogies? Do any exist? The ancient church fathers often followed Scripture’s lead in referring to Jesus Christ as the Word. The Greek term logos meant word, reason, or discourse. Consider how words functions in human cognition. We can have a verbal concept in our minds as a kind of separate entity. The mind can discourse with itself about the idea, which resides within the mind yet is distinct. While the word remains interior, it has a life of its own within ongoing mental discourse. However, it hasn’t yet made an exterior impact. Only when the speaker utters the word—sends it forth to communicate—does it start to achieve tangible things. When God wanted to create the world, he spoke the verbal command “Let there be light!” to fashion the cosmos (Genesis 1:3). And when God wanted to save the world from sin, “the Word (logos) became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). Of all the analogies of the Trinity, the idea of God’s Word works best to depict Christ because it has direct scriptural precedent.

To round out this idea, we can add the analogy of the Spirit as God’s Breath (ruach in Hebrew, pneuma in Greek). Although this isn’t exactly a “mental” analogy, it completes the idea of the Word by adding another interior aspect of God that can go forth in power. According to Scripture, the divine Breath exudes from God and accomplishes great things. Moses understood this after the Israelites crossed the Red Sea on dry land to escape from the Egyptians whom the sea consumed. “At the blast of your nostrils the waters piled up,” sang Moses. “The floods stood up in a heap . . . You blew with your wind (ruach); the sea covered them; they sank like lead in the mighty waters” (Exodus 15:8, 10). God didn’t have to send angels or armies to fight against Pharaoh. All he had to do was exhale. The God who speaks and breathes is the biblical analogy of the Trinity.

Analogy and Reality

A fair assessment of the Trinitarian analogies suggests they can all provide helpful illustrative value, some more so than others. However, none of them fully captures the infinite nature of God. They offer, at best, a partial glimpse of a mystery that is beyond our comprehension. That is why the wisdom of the Cappadocian father Gregory of Nazianzus is worth heeding. In one of his great theological orations, he concluded about the Trinity:

[T]here is nothing to satisfy my mind when I try to illustrate the mental picture I have, except taking [only one] part of the image and wisely discarding the rest. So, in the end, I resolved that it was best to have done with images and shadows, deceptive and utterly inadequate as they are to express the reality [of God]. I resolved [instead] to keep close to the more truly religious view and rest content with few words, taking the Spirit as my guide . . . To the best of my powers I will persuade all men to worship the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as the single Godhead and power, because to him belong all glory, honor and might for ever and ever. Amen.

Perhaps today’s Christians can agree with Gregory that humble worship, not precise explanation, is the true purpose for our contemplation of the Trinitarian God!

For more on the Trinity, see my new book, “The Story of the Trinity: Controversy, Crisis, and the Creation of the Nicene Creed.”

Thank you so much for your very adequate explanation of the Trinity. I do agree that humble worship is our best approach. I would add faith, hope and love and how they or God’s Word has helped me to appreciate his grace.

Thanks for all your writing, fiction, non fiction and a masterful blend of both.

I appreciate your kind words and I’m glad it blessed you!

Professor Liftin,

Thank you for this resource!

– Theology 201 student

Professor Liftin,

This was an interesting read! Thank you for this extra resource for a deeper dive into Theology!

-Theo 201_003 student

Interesting. I’ve never heard of the color model being an allegory used for the Trinity.

What do you think about the analogy of three in one shampoo?

Well, that’s an interesting idea! I suppose it could convey one substance with three distinct “roles.” However, some other analogies are more obviously threefold, whereas shampoo is sort of blended, so the distinctness of the three aspects is a bit obscured. The best analogies obviously convey three distinct Persons that don’t “disappear” into one another.

Thank you, Dr. Litfin. I look forward to reading your newest book on the Trinity as well.

– THEO201

I enjoyed reading through this and learning more about the Trinity!

Thank you Dr. Litfin!!

-Theology 201

Thank you for thinking so deeply and thoroughly about this most important of matters! God bless you Dr. Litfin.

– theo 201 student 🙂 section 003

Very helpful in visualizing the trinity!

Beautifully articulated. Truly blessed to be walking through this topic with you this semester.